You should check out this awesome craft cooperative started by these awesome people in Charlotte: www.makewelcome.org

Okay, they all happen to be friends of mine. All bias aside, though, it really is a great group of people meeting a felt need in this community, and showing so much love in the process. I get asked by students and neighbors all the time whether they can join the group, which now has a waiting list due to space and sewing-machine-access limitations.

Pray that it continues to grow into whatever God wants it to be...

Monday, November 18, 2013

Tuesday, November 12, 2013

Photos - Fall and San Diego

A couple weeks back, it was one of those amazing autumn Saturdays that begged to be photographed. It wasn't hard, fortunately--all of these photos were taken on the walk between my house and my Saturday coffee shop haunt.

Then last week I was down in San Diego, visiting one of my dear friends. I got to put my feet in the Pacific (sorry, the Atlantic just isn't the same), hang out in an unexpectedly spectacular cactus garden, and soak in the contrasts of sea and stone and trees all along the coast. Probably a hundred times I found myself wishing I had my real camera with me, but I tried to get at least a few decent shots with the camera on my phone.

The rest of the shots from both sets are on my flickr site.

(And yes, I do plan to write blog posts again, I promise!)

Then last week I was down in San Diego, visiting one of my dear friends. I got to put my feet in the Pacific (sorry, the Atlantic just isn't the same), hang out in an unexpectedly spectacular cactus garden, and soak in the contrasts of sea and stone and trees all along the coast. Probably a hundred times I found myself wishing I had my real camera with me, but I tried to get at least a few decent shots with the camera on my phone.

The rest of the shots from both sets are on my flickr site.

(And yes, I do plan to write blog posts again, I promise!)

Saturday, July 13, 2013

Zomi

During our Friday Bible study, my friend N.—the amazing woman who lets us meet in her home—shares her one Zomi Bible with her husband. They are a family of seven. They have one Bible. Their children have a few English Bibles, but they have only one in the language of their hearts.

We asked her if she knew where there were Bibles in Zomi. We would be happy to help her buy some for her family and any other Zomi speakers she knew who had no Bibles. She got it in Burma, she told us. She didn't know.

Even with the internet and other Bible-finding resources at our disposal, we couldn't find any. I have a friend who knows people high up in a translation organization, with connections to other organizations. She called him, who called a guy, who called a guy. No one could find Zomi Bibles. Finally, my friend was put in touch with someone who consults on Bible translations in the Zomi-speaking area of Myanmar. He thought he might be able to find a few, but he couldn't ship them to us—they wouldn't make it through the Burmese mail system. He found someone to take them by hand across the border into Thailand, and then ship them from there. The whole time we all hoped it was the right language, and the right dialect of the language (difficult to confirm long-distance).

The search started in May. Just yesterday, N.'s family was able to hold one more Bible in Zomi. They don't have to huddle together over one copy now, trying to read at the same time. It was beautiful to see how excited they were. It was beautiful to see their seventh-grade daughter—who diligently reads her English Bible, but struggles with the vocabulary and grammar of a language she's known only a couple years—visibly moved when she opened it. It was beautiful—and humbling—to see what a huge deal it is for them to read the words of God in the language they use to think and to pray and to talk to one another.

As I've mentioned, B. and my other Jarai-speaking friends don't even have the whole Bible translated into their language. They have to read it in English or in Vietnamese, the language of the people who persecuted many of them.

I can't imagine what that's like. I admit, even as a linguist, I take it completely for granted that I have access to almost anything I want in English.

I wish I could find Bibles for all my brothers and sisters here. I wish I could speak Zomi and Jarai and Nepali and Chin and Swahili and Karenni and Ringau, and could hear their insights, and could encourage and be encouraged by them in words we all understand. I hope that they are still encouraged as much as I am when we meet together, even without a common language.

God—the God of all languages and peoples and culture—is here. He is at work. He is bringing his Word here, even in cases where you can't just hop over to the bookstore and buy a copy of it. ...I feel so honored to get to see him working.

The image at the beginning of this post is a paper cutting I did recently, based on the unity of the global Church expressed in Ephesians 4. The background of each landmass is a list of (only some of!) the living languages found in those places. (Except Greenland—it has only two languages, so I stole some of Canada's for it.)

Sunday, June 23, 2013

Wait—You want to come inside?

I see a slight movement out the corner of my eye. I turn, and jump. Four eyes are staring in through the one small

crack in the mini blinds of my front window. I look closer and recognize B. and Y., two of

my Jarai-speaking friends, grinning in at me.

They're probably here about World Refugee Day, I think to

myself. We told all the students that a school

bus would be coming to take them to the celebration downtown. They know I'm going to ride the bus with

them, to help with logistics, and have been asking me about it all week.

I walk out onto my stoop to greet B. and Y., and, sure enough, they're

at my house to double-check they know the right time and place.

"Yes," I tell them. "Across the street at

3:30." They smile and nod and say

"Okay"—and continue to stand on my stoop.

Right, I tell myself. This

"isn’t America." There aren't

any thirty-second conversations, or "I just had a quick question"

comings and goings. This is my cue to

invite them inside to visit.

I pause.

It's Saturday, and I've been doing projects around my house—painting curtain

rods, rabbit-proofing my back patio, making greeting cards, reorganizing part

of my kitchen—and my home is in chaos.

My curtains are on the floor, my furniture is disarranged, art supplies

are strewn about, there's a pile of "stuff to take upstairs" on my

stairway, I haven't done the dishes yet, paint fumes are coming from outside,

and there's a hacksaw on my kitchen table.

It's always hard for me to let someone see my house when it's

messy. True story: I was sick a few

months ago, and my drugged, half-asleep brain realized that if I died,

people would come inside and see the I'm-sick-and-don't-care-if-stuff-is-everywhere

state of my house, and think I lived that

way. I actually dragged myself out of

bed and began neatening before eventually deciding it wouldn't matter to me

anymore, since I would be dead. (Yes, I

completely blame my mother for this.)

Needless to say, I was appalled at the thought of these two friends—neither

of whom had been inside my apartment before—seeing my mess. I knew, though, that inviting them in was

important. It was important for them,

culturally and relationally, as a sign of respect and friendship. But it was important for me, too. As I've said before, hospitality does notcome naturally to me. This was a chance

for me to choose whether it was more important to show love or to bow to my vanity—to

think of my guests, or to think of myself.

With some mortification and a quick prayer against my own pride, I invited

them inside (not to say I didn't kick a couple things under the couch and shove

some of the furniture back where it went on my way to the door).

And you know what? It was

fine. The visit itself was endearingly

awkward and amusing, as most such visits are.

This is the same B. you may remember, who invited me into her house

before. The B. who speaks essentially no

English. Y. speaks even less. But I have tons of family pictures (always a

popular choice), they gave me a tour of Vietnam on a world map, and we enjoyed

just being together, words or not.

Here's the best part: While they were there, I even forgot (sometimes) that

my house was "embarrassing."

In a weird way, I can see the grace in God dropping me straight into my

mind's worst-case scenario for a spontaneous guest: If a visit can still go

well in that chaos, then it can work in any setting. Yesterday was for me a confirmation—an actual

successful experience, however small it may seem to you, for me to remember and

build from and hold onto—that hospitality is not about how well I can impress

people with my house, or my food, or my "hostess-ness." It is not about me at all. It's about sharing the love of Christ, and

letting him love people and meet their needs through my obedience to him.

So—while still slightly horrified that people were in my house

yesterday—I'm glad that God is giving me opportunities to learn to be more

hospitable. I'm even more glad, again,

that he's a patient teacher.

A quick follow-up on World Refugee Day:

While B. and Y. were at my house, other students began gathering

outside my door, too.

Now, if any of you have traveled outside the U.S., you are probably

familiar with varying views of time across cultures. We were fully expecting our day to unfold in

"refugee time"—we told them the bus was leaving at 3:30 when it was

actually coming at 3:45. Our optimistic

departure time was 4.

It was 2:30 when they started gathering. By 2:45, a whole group was standing in the apartment

parking lot, waiting for me to walk to the bus site with them. It was amazing. They were so excited to celebrate.

At the event itself, people walking by downtown were drawn to the

beautiful cultural costumes and dances, and stopped to ask questions about what

was going on. Many had never heard of refugees, or had no idea that more than

3,000 of them lived right in Charlotte.

All in all, it seems to have been a great success, both as a cultural

celebration and awareness-raising campaign.

My neighbors are already planning for next year—some are planning to get

me and the other ESL teachers/volunteers to do a Bhutanese dance with them. That will be interesting…

Thursday, June 20, 2013

World Refugee Day

It's World Refugee Day today. All over the world people are taking a moment to look around and recognize the courage and resilience of the millions of refugees around them. There are more than 43 million refugees (people who have fled their countries due to violence or disaster) and internally displaced people (people who are still in their own countries, but have fled their homes) worldwide.

This year in Charlotte, we're having a festival-style celebration to help Americans better understand their new neighbors, and to give the refugee community the chance to share their cultures with us. Most cities have some sort of celebration or awareness campaign—be on the lookout this weekend, wherever you are!

This year in Charlotte, we're having a festival-style celebration to help Americans better understand their new neighbors, and to give the refugee community the chance to share their cultures with us. Most cities have some sort of celebration or awareness campaign—be on the lookout this weekend, wherever you are!

Tuesday, June 11, 2013

Photographs of Light Bulbs Exploding With Things Inside Them

I get wickedly distracted by art and design rss feeds and the various gawker sites. The other day I stumbled across Jon Smith's photography in one of them:

How amazing are these? There are more here. It just makes me so happy that there are creative people like this, making really normal things so fascinating and beautiful. Enjoy!

Tuesday, May 14, 2013

Providence

I look in every pocket of my bag twice. "Hang on," I tell the friend I'm meeting, "I think I left my wallet in the car." I check the front seat. No wallet. Back seat. No wallet. Under all seats. Trunk. Bag, again.

No wallet.

"Did you come straight here from your house?" my friend asks.

"Yes. I remember I had it in my hand on my way out." I think through my trip from house to coffee shop: Walking from my apartment to the car, wallet in hand. Realizing I'm low on gas. Stopping to fill my tank. Setting my wallet on the closed trunk to free up both hands to open my stuck gas cap.

... Driving away with the wallet still on the closed trunk of my car.

- sinking feeling -

Millisecond of hope: Maybe it's still there, at the gas station?

- deeper sinking feeling -

The gas station is more than thirty minutes from the coffee shop, and—remembering the general aura of its location—I am not hopeful. I figure I might as well call, though, to see if it was turned in. The woman who answers the phone is much more helpful than I expected, and even goes out to the gas pump I used to see if it's on the ground. No wallet.

Call-waiting comes in on my phone while we're talking, with an unknown number. Maybe someone found my wallet?! But my phone number isn't in there, so how...? I call the number back, somewhat puzzled.

A very friendly voice answers. "Oh, hi! Is this Marybeth calling back? This is N. at Insurance Company—someone found your wallet and our card was in there, so he called us hoping we could contact you. He left his name and number if you want to call him and arrange to get it back."

I am astounded. I call the number she gives me, and he does in fact have my wallet. It turns out that he saw it in the middle of the intersection by the gas station, recognized it as a wallet, and turned around so he could pull over and retrieve it. ("I'm sorry, I think some of what you had in there may have fallen out—there was too much traffic for me to get all of it," he tells me. Um, you're apologizing that you didn't risk your life darting around a major road to gather every scrap of paper from a stranger's lost wallet? Seriously, please, no worries.) He then spent a good part of half an hour trying to track me down, including stopping by my apartment, and then drove out of his way to meet me at a shopping center to return it.

I lost a few gift cards (probably what went flying out) and I think a car or two may have run it over, but I have my wallet back—complete with credit cards, license, and even my cash (okay, it was only two dollars—but both were still there!).

So, while it's in no way sufficient since I'm sure they don't read this blog: cheers to the guy who put so much effort into returning my wallet today, and to N. at my insurance company for being willing to help (and checking back in with me to make sure it worked out), and to the woman at the gas station for at least taking the time to look around. They all made a potentially-very-stressful-situation into an amazingly-not-stressful one.

And yay God, hey? I am so glad to have it back. (I'm going to miss my just-filled coffee shop gift card, though. Sigh.)

No wallet.

"Did you come straight here from your house?" my friend asks.

"Yes. I remember I had it in my hand on my way out." I think through my trip from house to coffee shop: Walking from my apartment to the car, wallet in hand. Realizing I'm low on gas. Stopping to fill my tank. Setting my wallet on the closed trunk to free up both hands to open my stuck gas cap.

... Driving away with the wallet still on the closed trunk of my car.

- sinking feeling -

Millisecond of hope: Maybe it's still there, at the gas station?

- deeper sinking feeling -

The gas station is more than thirty minutes from the coffee shop, and—remembering the general aura of its location—I am not hopeful. I figure I might as well call, though, to see if it was turned in. The woman who answers the phone is much more helpful than I expected, and even goes out to the gas pump I used to see if it's on the ground. No wallet.

Call-waiting comes in on my phone while we're talking, with an unknown number. Maybe someone found my wallet?! But my phone number isn't in there, so how...? I call the number back, somewhat puzzled.

A very friendly voice answers. "Oh, hi! Is this Marybeth calling back? This is N. at Insurance Company—someone found your wallet and our card was in there, so he called us hoping we could contact you. He left his name and number if you want to call him and arrange to get it back."

I am astounded. I call the number she gives me, and he does in fact have my wallet. It turns out that he saw it in the middle of the intersection by the gas station, recognized it as a wallet, and turned around so he could pull over and retrieve it. ("I'm sorry, I think some of what you had in there may have fallen out—there was too much traffic for me to get all of it," he tells me. Um, you're apologizing that you didn't risk your life darting around a major road to gather every scrap of paper from a stranger's lost wallet? Seriously, please, no worries.) He then spent a good part of half an hour trying to track me down, including stopping by my apartment, and then drove out of his way to meet me at a shopping center to return it.

I lost a few gift cards (probably what went flying out) and I think a car or two may have run it over, but I have my wallet back—complete with credit cards, license, and even my cash (okay, it was only two dollars—but both were still there!).

So, while it's in no way sufficient since I'm sure they don't read this blog: cheers to the guy who put so much effort into returning my wallet today, and to N. at my insurance company for being willing to help (and checking back in with me to make sure it worked out), and to the woman at the gas station for at least taking the time to look around. They all made a potentially-very-stressful-situation into an amazingly-not-stressful one.

And yay God, hey? I am so glad to have it back. (I'm going to miss my just-filled coffee shop gift card, though. Sigh.)

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Unity

There is one body and one Spirit—just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call—one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.

Ephesians 4:4-6

Let the word of Christ richly dwell within you, with all wisdom teaching and admonishing one another with psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with thankfulness in your hearts to God.

Colossians 3:16

"What's…" I hesitate, trying to guess the pronunciation,

"lah-teh?"

N. looks up at me, and I repeat the question, pointing to the Zomi word

"Late," at the top of the page.

She shakes her head and laughs her "I don't know—no English" laugh.

She flips to the table of contents and we look at it together. With some

referencing and counting, I figure it out.

"Oh, Psalms!"

"Psalms," she repeats. "Late. Psalms."

How can we encourage unity in the Church, across so many languages

and cultures? How can we have fellowship when we can't even talk to each other?

These are questions I often ask myself when I pray for this community. There

are many Christians here, but—understandably—they (we) tend to spend the most

time with other believers of like-language. Yet while I advocate first-language

Biblical teaching and fellowship whenever it's possible, the Church is also this

mysterious thing that does transcend language and culture. These believers

I see, these believers who can't say more than "hello" to me or to each

other, are brothers and sisters. We are united in Christ. But how, how do we

live out that unity?

As a step towards it, A. and I invited

several women over to my house, to read the Bible and pray and at least

physically be together. Turns out that

N.—a Zomi speaker from Burma—was the only one who could make it. Her English

proficiency is quite low (although much higher than our Zomi proficiency!), but—all

nervousness aside—I think she was as eager to meet with us as we were to meet

with her. We read a story in Genesis, each of us following along as we

alternated between Zomi and English, and then there was a pause. This is where,

in an English Bible study, we would share thoughts or ask questions or make

observations. Eventually, A. and I each said a thing or two in the simplest English we

could, but we could tell N. couldn't really understand us. And she had an

all-too-familiar expression of frustration on her face, of thoughts and ideas

to offer and no language to share them.

There was another pause, then something beautiful happened. N.'s face

brightened, and she began flipping purposefully through her Bible. She pointed

to the passage she found, and—once we figured out that "Late" was "Psalms"—A.

and I were able to find the same passage in English as she read aloud in Zomi. The

passage went along with one of the themes of the Genesis story we had read, and

I could see the connection she had made between them. The psalm reminded me of

something I had read earlier that week, and we all flipped there together. And

that's how the next two hours unfolded: the three of us side by side,

cross-referencing and pointing and reading together, communicating through the words

of our shared God.

This last week, we met at N.'s house instead of mine. When I arrived,

the living room was already full: A., N., N.'s husband and sixth-grade daughter,

another Zomi-speaking woman, a Jarai-speaking neighbor, and another American, were

all sitting together with their Bibles out. Again, we all just read and prayed

and pointed out meaningful passages to each other. Bl., the only Jarai speaker

there, can't read in any language and understands even less English than N.,

and yet even she seemed fully engaged and wants to come back.

No, we didn't "study" the Bible in the traditional, American

sense of the word. We didn’t apply hermeneutics or discuss theology, or look at

the historical factors surrounding any given passage, or ask application

questions. But it was one of the richest "Church" experiences I've

ever had: three languages, three cultures, eight people with no reason to meet except

the shared loved of the same Savior, spending time seeking him together. The chance

to see what connections the eyes of different cultures saw between passages, and

which verses were important to them—a tiny glimpse of how God is speaking to

them and the thoughts I wish they could share with me. English, Jarai and Zomi

all voiced in prayer in a Zomi home.

Yes, it's only eight people, out of hundreds. But unity has to start somewhere…

Monday, April 29, 2013

Patience, hard thing

Patience, hard thing! the hard thing but to pray,

But bid for, Patience is! Patience who asks

Wants war, wants wounds; weary his times, his tasks;

To do without, take tosses, and obey.

Rare patience roots in these, and, these away,

Nowhere. Natural heart’s ivy, Patience masks

Our ruins of wrecked past purpose. There she basks

Purple eyes and seas of liquid leaves all day.

We hear our hearts grate on themselves: it kills

To bruise them dearer. Yet the rebellious wills

Of us we do bid God bend to him even so.

And where is he who more and more distils

Delicious kindness?—He is patient. Patience fills

His crisp combs, and that comes those ways we know.

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889), Untitled, pub. 1918

But bid for, Patience is! Patience who asks

Wants war, wants wounds; weary his times, his tasks;

To do without, take tosses, and obey.

Rare patience roots in these, and, these away,

Nowhere. Natural heart’s ivy, Patience masks

Our ruins of wrecked past purpose. There she basks

Purple eyes and seas of liquid leaves all day.

We hear our hearts grate on themselves: it kills

To bruise them dearer. Yet the rebellious wills

Of us we do bid God bend to him even so.

And where is he who more and more distils

Delicious kindness?—He is patient. Patience fills

His crisp combs, and that comes those ways we know.

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889), Untitled, pub. 1918

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Mental Health First Aid

March was crazy busy for many reasons, but at least I have something to show for it: I'm now officially certified in mental health first aid.

What, you may ask, is that?

You're all familiar with physical first aid, I assume. Mental health first aid is the same idea: I've been trained to recognize and appropriately respond to mental health crises of various kinds. It's not like I'm suddenly an expert, and can go around diagnosing people or giving them therapy—just like physical first aid certification doesn't equate to a medical degree—but I've been given the tools to be a "first responder," to help deescalate situations and direct people to further help if necessary.

The training I attended was specifically geared towards people who work within the refugee community. Some of them work for resettlement or aid agencies, and most of them are members of the various ethnic groups represented here—they're leaders in the Bhutanese, Burmese, Vietnamese, and Middle Eastern communities.

It was a helpful session to attend, because the fellow trainees were able to help address a problem that we as Americans often face: How to adapt western perspectives of mental health cross-culturally. We can see, for example, that community X has a really high incidence of severe depression, but also know that community X doesn't recognize the existence of mental illness. Or we can see that individual Y is showing classic signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, but also know that her community will shun her if she even acknowledges any "mental problems," much less seeks treatment for them.

For me, and the other Americans I've met in this situation, the concern is not whether people of other cultures switch to a western approach to mental health. We aren't interested in making people use our mental health terminology or go to talk therapy or take medications that violate their religious principals. We care about giving people who are debilitated by what we call depression, or anxiety, or post-traumatic stress the tools they need to function in every day life.

The problem is, we don't really know what those tools look like yet. Even the people I mentioned above, who are themselves part of these cultural communities, don't know what those tools look like. It is encouraging, though, to see that the dialogue is taking place—that the tools are being sought.

There is so much pain and loneliness and fear in the lives around me. I, of course, continue to pray as well, that the people around me would experience the healing and hope that only Jesus can bring. He is so desperately needed here.

Monday, February 18, 2013

"Can I come for conversation?"

"Teacher, can I ask you question?" The voice is quiet, and

hesitant.

I look up and smile at M. I've helped her a couple times after class

with doctor's forms and mail questions, so I expect that she has some kind of

paperwork for me to look at. She doesn't.

"Teacher, can I come to your house sometime for conversation? I

want speaking English good, and my home no one help me."

I'm delighted—"Of course!"—but surprised. M. is one of the

shyest students in the higher level class where I volunteer. She is picking up

English really fast, but she isn't convinced—she rarely offers an answer even

when she's right, and she speaks so quietly it's often hard to hear what she's

saying.

Most of the students in that class are either from Bhutan or Vietnam. M.

is not—she's from East Africa, and no one else in the class speaks her first

(or second) language. Most of the students have large extended families and a

fairly strong community here. M. does not—she is here with only her

elementary-school-aged son, who is gone all day at school and various after

school programs. She doesn't have a job. She can't drive a car. She has, I

think, one cousin somewhere nearby.

She's lonely.

I'm so proud of her for asking to practice English with me.

She stopped by my house once, because we needed to use my computer to

renew her state ID. I'm glad that she felt welcome enough that she wants to

come back. I'm glad to have her into my home, and to have this opportunity to

show love to her, and—hopefully—to become friends.

I'm also somewhat terrified.

I barely feel competent at small talk with other English speakers. M.

is not only a non-native speaker, but a shy one. I have no idea what we're

going to talk about.

I'm an introvert. "Hospitality" is a concept I have struggled

with my whole adult life. I love people, and theoretically I really like having

them over, but—when it comes down to actually doing it—I get super stressed

about and exhausted by the whole thing. It embarrasses me how stressful I find it, in

fact.

Add the cross-cultural dimension, and I stress out even more. Is she

expecting a short chat or a four-hour visit? Visits usually involve

food—should it be a full meal? Which foods, again, does her religion forbid? Is

it her culture that gets really offended by X? Or is it if you don't do Y? How

much should I make this visit about "learning American culture" and

how much should I make it about "meeting cultural expectations" so

she's comfortable? And seriously, what are we going to talk about?

When I was deciding whether to move here, to live with refugee

neighbors, I knew that inviting people into my home would be important. Hospitality

is a really big part of most of these cultures, and even without that, it's a

very normal step in relationship-building. For me, though, it was definitely on the

"not my strength at all / fills me with vague terror" list.

While I was praying through it, I was convicted about

something: I tell myself that I get stressed out because I really want my

guests to feel comfortable, and to have a good time. What I'm actually

stressed about, though, is my guests' perception of me as their host—whether

they will leave thinking about how awesome I was at making them feel at home,

or leave thinking I failed.

It's a subtle but vital difference. One is guest-focused, one is

me-focused.

I also know the only way I can let go of that need to focus on myself

and others' perception of me is to be firmly rooted in the truth of who I am in

Christ—the truth that I don't need others' approval, the truth that I am known

and accepted by the Person who is great enough to speak the stars into

existence and intimate enough to know them each by name, the truth that he is

my glory and the lifter of my head, the truth that his power is made perfect in

my weakness, the truth that I am not big or important enough to ruin his plans,

and the truth that he loves me completely in that smallness.

Unfortunately, it seems to be a slow process. I repeat truth to myself,

but I still often fear. I have had moments where the greatness/intimacy of God

and my security in him have been so obvious, I wonder at my fear—moments where

"what can man do to me?" actually is the completely rhetorical

question it's meant to be—and then the moment has passed and I'm back to

craving the approval of people.

So, I am covering these coming visits in prayer. Prayer for M., that

that she will feel welcome and at peace and encounter God's presence here, and

prayer for myself, that I would rest in truth and love M. instead of worrying

about myself and what she thinks of me.

Feel free to join in.

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

I just live here.

It seems that in fact we live as if we should give as much of our heart, soul, and mind as possible to our fellow human beings, while trying hard not to forget God. At least we feel that our attention should be divided equally between God and neighbor. But Jesus' claim is much more radical. He asks for a single-minded commitment to God and God alone. God wants all of our heart, all of our mind, and all of our soul. It is this unconditional and unreserved love for God that leads to the care for our neighbor...

My call is not to serve the poor. My call is to follow Jesus. I have followed Him to the poor.

- Henri Nouwen, Show Me the Way (emphasis added)

My call is not to serve the poor. My call is to follow Jesus. I have followed Him to the poor.

- Mother Theresa

I sometimes get stressed out during very normal-seeming conversations.

People find out I "work with refugees," and—this is the good part—they

ask lots of questions. I love it when people are interested in this sometimes

invisible-seeming population. I love hearing that people want more information,

and want to be involved. I could talk about global refugee issues and the specific

community here and individual refugees and cross-cultural interactions all day.

The problem is when they ask me about what I actually do. Their

questions echo the questions I've been asking myself since I moved here. I feel

this pressure, real or imaginary, to justify the fact I've been here five months,

and I don’t have any more of a defined goal, or a "ministry model,"

or a vision for large-scale need-meeting, than I did when I arrived. Assuming

that people expect plans and details, I panic slightly:

"Um, no, I'm not officially here with an organization."

"Well, I just got here recently and am still getting a sense of

the community, what's already here, and figuring out where I fit… [enter

nervous rambling]"

"Well, 'what I do' is kind of vague at this point. I'm

volunteering in some English classes, and trying to build relationships… [more

nervous rambling]"

"Um, it's actually kind of hard to identify one greatest need in

this community, so, no, I don't actually have a plan for meeting it… [increasingly

self-conscious rambling]"

"I don't know." [feeling defeated] "I just…live here."

This week, though, I realized something: I do "just live

here," and that's not a bad thing.

I also remembered something: God did not call me to Charlotte to start

a refugee assistance program, or develop a productive ministry model, or even

to identify and meet needs. God did not call me to Charlotte to help refugees,

at all.

God called me to Charlotte to do exactly what I was created to do: To

follow him. To seek his face. To give him glory. To depend on him. To love him

with all my heart and soul and mind and strength.

God tells me that, loving him, I should love my neighbor. I followed

him to a place where most of my neighbors—figuratively and literally—happen to

be refugees. They're the people he's placed around me, for me to love, and

that's what I'm trying to do.

It's not really any different than in the past, when my neighbors were suburban

families or blue-collar workers or grad students or office coworkers. The way

to show love might look a little different each place—here, it may be

helping someone read a doctor's form, or English conversation practice, or introducing

the wonders of over-the-counter decongestant—but both the source and purpose of

the love are the same.

I have nothing against structure, or organizations, or programs. I

think they could prove useful here. It won't surprise me if I up up

involved with them somehow. I just want to get the order of things correct: If

God is leading me to join or establish some kind of program, then I pray that I

hear and see that and follow him wholeheartedly into it. If he's not, then I pray

that I won't join or establish one simply to feel useful, or to have something

productive-sounding to say during small talk, or even to meet actual needs.

My call is not to meet needs. My call is to follow Christ.

So, for now, I just live here.

I live here, seeking God's face and seeking God's will, knowing that—although

I sometimes get confused and stumble off in the wrong direction—the God I seek

is patient and slow to anger, and remembers that I am dust.

I live here, working, and doing dishes, and paying bills, and making

friends, and trying to love my neighbors, and sometimes failing, but always—amazingly—covered

in and sustained by grace.

I live here, hoping that my neighbors will see God's love through my

life among them.

"Love the Lord your God with all

your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind." This is the first and greatest

commandment. And the second is like it: "Love your neighbor as

yourself."

Matthew 22:37-39

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

A Place

Do you know what would be amazing? A place where the believers in this neighborhood—English and non-English speakers alike—could come together and grow as the Body of Christ. Where refugees and Americans could receive Biblical teaching and fellowship in their own languages, but could also be unified and edify one another across languages. Where people with practical needs could go and know that they would be shown God's love, even before they know that's what they're experiencing.

So, do you know what would be amazing? A church here.

Don't misunderstand me—the Church is already in this neighborhood. There are believers here from multiple continents and languages, who are loving and growing and ministering.

There's a house church of more than fifty Jarai speakers that meets down the street from me, crammed into a tiny apartment. The host/pastor of these people approached us recently, asking if we knew a bigger place they could meet. We haven't found one.

There are people here who have only a few other believers who speak the same language. They want to join American Bible studies, but the language is too high and fast for them, or the churches are too far away. Most people here rely on walking as their only consistent transportation.

Now, this is the American South. There are already many churches—church buildings—in this neighborhood. Granted, I haven't visited every single one, but there doesn't seem to be one that has actively embraced this community as brothers and sisters. There doesn't seem to be much interest in helping meet practical needs. Honestly, there doesn't seem to be a lot of love in these churches in general.

So often, we find ourselves thinking "X could happen and it would be awesome, if only we had a place to do it."

I know that God is big. Far bigger than I let him be, most of the time. I don't know whether his answer to this will be to give us a brand new place, or to transform the hearts in one the churches already here, or whether we need to keep waiting, or something else we haven't thought or imagined. I do know, however, that there a couple properties for sale in this neighborhood. To us, they seem ideal, space- and location-wise. We're excited to be looking into them, and seeing them as possibilities; but we also know that what seems perfect to us, with our limited vision, is not always what God knows to be perfect.

So, please pray with us, for wisdom and faith and patience and boldness as we listen to what God wants to do here. Pray about these properties, that it would be clear whether to pursue them. Pray that we would hold our ideas and hopes with open hands, and remember that God loves this community more than we ever could, and that he wants his glory to spread here even more than we do.

...It would be so helpful to have a place.

So, do you know what would be amazing? A church here.

Don't misunderstand me—the Church is already in this neighborhood. There are believers here from multiple continents and languages, who are loving and growing and ministering.

There's a house church of more than fifty Jarai speakers that meets down the street from me, crammed into a tiny apartment. The host/pastor of these people approached us recently, asking if we knew a bigger place they could meet. We haven't found one.

There are people here who have only a few other believers who speak the same language. They want to join American Bible studies, but the language is too high and fast for them, or the churches are too far away. Most people here rely on walking as their only consistent transportation.

Now, this is the American South. There are already many churches—church buildings—in this neighborhood. Granted, I haven't visited every single one, but there doesn't seem to be one that has actively embraced this community as brothers and sisters. There doesn't seem to be much interest in helping meet practical needs. Honestly, there doesn't seem to be a lot of love in these churches in general.

So often, we find ourselves thinking "X could happen and it would be awesome, if only we had a place to do it."

I know that God is big. Far bigger than I let him be, most of the time. I don't know whether his answer to this will be to give us a brand new place, or to transform the hearts in one the churches already here, or whether we need to keep waiting, or something else we haven't thought or imagined. I do know, however, that there a couple properties for sale in this neighborhood. To us, they seem ideal, space- and location-wise. We're excited to be looking into them, and seeing them as possibilities; but we also know that what seems perfect to us, with our limited vision, is not always what God knows to be perfect.

So, please pray with us, for wisdom and faith and patience and boldness as we listen to what God wants to do here. Pray about these properties, that it would be clear whether to pursue them. Pray that we would hold our ideas and hopes with open hands, and remember that God loves this community more than we ever could, and that he wants his glory to spread here even more than we do.

...It would be so helpful to have a place.

Now to him who is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think, according to the power at work within us, to him be glory

in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations,

forever and ever. Amen. - Ephesians 3:20-21

in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations,

forever and ever. Amen. - Ephesians 3:20-21

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Refugee Backgrounds: The Bhutanese

Many of you have asked me who my neighbors are, where they're from, and why they're here. I've decided to spotlight some of them for you, starting with the Bhutanese.

At a glance:

Country of origin - Bhutan

Refugee camp country - Nepal

Primary language - Nepali

Primary religion(s) - Hindu (some Buddhist, a few Christians)

Primary reason for leaving their home country - Ethnic oppression

Total number of refugees - Almost 58,000 as of Jan 2012

Resettled in Charlotte* - More than 2,200 as of Dec 2012

Total number of refugees - Almost 58,000 as of Jan 2012

Resettled in Charlotte* - More than 2,200 as of Dec 2012

Although it's true

when I say that the refugee population in Charlotte is from "all

over"—including people from Burma, Vietnam, Somalia, Iraq, Eritrea, Congo,

and Afghanistan, among several others—most of the new arrivals, including

almost all of my neighbors, are from Bhutan.

Many Americans mistakenly call these people Nepali instead of

Bhutanese, and the confusion is understandable.

My neighbors speak Nepali, not Dzongkha (the official language of Bhutan). They wear Nepali clothes

and practice Nepali cultural customs. Ask any of them, though, and they

will tell you clearly and proudly: they are from Bhutan. Not Nepal.

So, how did they get here?

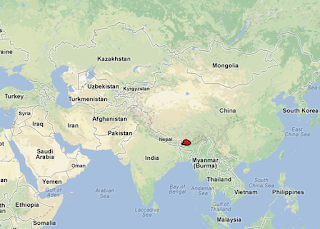

Bhutan is a small country in south Asia, north of India and Bangladesh and east of Nepal.

In the

late 1800s, people from Nepal began migrating into the farmland in southern

Bhutan. They didn't have very much

contact with the Bhutanese in the north, so they retained their Nepali

language, culture and religion. The cultural

differences didn't really cause conflict, though, at least at first, and Bhutan

became their home. By the mid-twentieth

century, they considered themselves thoroughly Bhutanese—they were simply ethnically

Nepali Bhutanese instead of ethnically Bhutanese Bhutanese.

In the 1980s, though, the Bhutanese ruling majority began to feel

threatened by the growing number of Nepali-speaking "Lhotsampas"

("People of the South"), and began a campaign of "Bhutanization":

they outlawed the Nepali language, instituted dress codes, stripped many of the

Nepali-speakers of their citizenship (or refused to recognize that they had

ever had it in the first place) and civil rights, and removed them from

positions of political and cultural influence.

Protests in the late 1980s and 1990 led to violent encounters between

the two groups, and in 1990 tens of thousands of ethnic Nepalis were forced to

flee the country into Nepal and India.

Since 1990, thousands of Nepali-speakers have been sitting in

refugee camps, waiting to be allowed back into Bhutan.

If they are ethnically and culturally Nepali, you may ask, why don't they just settle in Nepal? Two of the simpler reasons in this complex issue: 1) the Nepali government won't let them integrate (refugees are rarely allowed to leave the camps or hold jobs), and 2) they don't want to settle in Nepal, because they aren't Nepali. They're Bhutanese. (Being "American" is a huge part of your identity, right? This would be roughly like the White House suddenly telling you and all your neighbors that you're not Americans and aren't allowed to live here anymore, because your ancestors came from (we're pretending) Canada a hundred years ago. Even though Canadians speak English and share some cultural similarities, would you shrug and say "Fine, okay, I'm Canadian now"?)

Unlike many other refugees who know they have left their home countries permanently and are relatively eager to leave camps and resettle, ongoing (yet fruitless) talks between the governments of Nepal and Bhutan and the UN have left most of the Bhutanese refugees in limbo—with just enough hope that they'll be allowed to return home that they are reluctant to resettle into new countries. They want to be ready and nearby "when they are allowed back into Bhutan." Many Bhutanese refugees also seem to see third-country resettlement as a political and cultural insult. For them, a return to Bhutan is the only just—and therefore the only acceptable—outcome.

If they are ethnically and culturally Nepali, you may ask, why don't they just settle in Nepal? Two of the simpler reasons in this complex issue: 1) the Nepali government won't let them integrate (refugees are rarely allowed to leave the camps or hold jobs), and 2) they don't want to settle in Nepal, because they aren't Nepali. They're Bhutanese. (Being "American" is a huge part of your identity, right? This would be roughly like the White House suddenly telling you and all your neighbors that you're not Americans and aren't allowed to live here anymore, because your ancestors came from (we're pretending) Canada a hundred years ago. Even though Canadians speak English and share some cultural similarities, would you shrug and say "Fine, okay, I'm Canadian now"?)

Unlike many other refugees who know they have left their home countries permanently and are relatively eager to leave camps and resettle, ongoing (yet fruitless) talks between the governments of Nepal and Bhutan and the UN have left most of the Bhutanese refugees in limbo—with just enough hope that they'll be allowed to return home that they are reluctant to resettle into new countries. They want to be ready and nearby "when they are allowed back into Bhutan." Many Bhutanese refugees also seem to see third-country resettlement as a political and cultural insult. For them, a return to Bhutan is the only just—and therefore the only acceptable—outcome.

Some of them, of course, are glad to leave the camps for America. One of my Bhutanese neighbors is my age, and wanted to come—she's excited about learning English and the educational and job opportunities

here. She came, though, with just her

aunt. The rest of her family wanted to

stay near Bhutan. She doesn't think they'll ever come to join her.

All refugee situations are sad, but something about the Bhutanese

story is particularly sad to me. I think

it's the sense of lingering, unrealized hope—it's almost certain that they won't be

allowed back into Bhutan, but not so certain that the hope has really

died. They keep getting told,

"maybe soon," which, to me, sounds like the worst place to be. I would rather just be told flat out that I couldn't

go back, so I could be free to move on. Maybe

it's my American need for closure.

I honestly don't know the individual stories of most of my

Bhutanese neighbors at this point. Most

of them aren't proficient enough in English to really tell me yet. I don't know whether the majority of them

actively wanted to resettle in America or were pressured into it.

What I do know? I know that most of them are farmers (and that they find my lack of agricultural knowledge both appalling and hilarious). I know that many (although not all) of them are Hindu. I know that many of them have seen and suffered horrible things. I know that many of them find city life overwhelming at times (even though America and Charlotte are usually both "good! [big grin]"). I know that they almost always smile at me and that they love their children and grandchildren.

What I do know? I know that most of them are farmers (and that they find my lack of agricultural knowledge both appalling and hilarious). I know that many (although not all) of them are Hindu. I know that many of them have seen and suffered horrible things. I know that many of them find city life overwhelming at times (even though America and Charlotte are usually both "good! [big grin]"). I know that they almost always smile at me and that they love their children and grandchildren.

And I know absolutely for certain from every one of them—limited English or not—that they are Bhutanese. Not Nepali.

----------

Although I've pieced together this Bhutanese history from several sources, the dates and whatnot above are mostly from Bhutanese Refugees in Nepal, as published by the Cultural Orientation Resource Center (COR Center) in 2007.

Further info:

UNHCR - Bhutan

COR Center - Bhutanese Refugees

Map of Bhutanese arrivals to the U.S.

*A note on resettlement numbers: It's hard to track refugee numbers accurately, because people are often resettled in one city and then quickly move to another city or state to join family, etc. This 2,200 accounts only for those refugees resettled into Charlotte straight from the camps, not those who may have moved here (or away) since.

Further info:

UNHCR - Bhutan

COR Center - Bhutanese Refugees

Map of Bhutanese arrivals to the U.S.

*A note on resettlement numbers: It's hard to track refugee numbers accurately, because people are often resettled in one city and then quickly move to another city or state to join family, etc. This 2,200 accounts only for those refugees resettled into Charlotte straight from the camps, not those who may have moved here (or away) since.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)